The story of Manon – in literature, film and pop

One of the earliest literary imaginings of a femme fatale, Manon has sparked the imagination of artists and their public across eras and genres – including choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, whose ballet you can rent on Ballet on Demand.

Check out this timeline of works of art (high and popular) inspired by the immortal heroine.

1731

L’Abbé Prévost publishes the novel L’Histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut.

It tells the story of a well-meaning young man, Des Grieux, led astray by his love for a young woman, Manon, who he finds irresistible. Many other men also fall for her – some willing to buy her off with a luxurious lifestyle. The original Material Girl, Manon cannot resist their offers. But she has Des Grieux wrapped around her finger, driving both of them to perdition.

Full of twists, the plot includes gambling, theft and prostitution, and Manon is a character so unscrupulous that the book proved too scandalous for its time: it got banned in 1733 and 1735.

In 1753 its writer published a new edition, with a foreword warning its readers that this tale is “a terrible example of the force of passions”. Quite. Even today, the book is regularly on the curriculum of French high school students.

1830

Dancers Joseph Mazilier and Amelie Legallois, 1830

Jean-Louis Aumer mounts the first ballet version of the story, for Paris Opera Ballet, with music by Fromental Halevy.

Further ballets are created in 1846 (by Giovanni Casati, music by Vincenzo Bellini, at Teatro Alla Scalla: it ends happily, with Manon and Lescaut marrying), and 1852 (Giovanni Colinelli, music by Matthias Trebinger).

1856

The first opera based on the story is composed by Daniel Auber. The story deviates slightly from Prévost’s novel, and this opera is not performed often. It features a popular aria for coloratura sopranos called C’est l’histoire amoureuse, also known as The Laughing Song:

1884

Jules Massenet composes an opera based on the story: Manon – his most popular. Hear one of its most notable arias called Adieu, notre petite table. In it, Manon remembers her happy, carefree days with Des Grieux when they shared meals at “our little table”: “Will the future have the charms of those beautiful days already passed”, she asks. (Sadly not, in her case).

Ten years later he would write a one-act sequel, Le portrait de Manon, where Des Grieux is now an old man.

1893

Giacomo Puccini also writes an opera, this time called Manon Lescaut, which premieres in Turin. It shows how extraordinary Manon’s story is that it would inspire three operas, two of which remain very popular to this day.

“Manon is a heroine I believe in and therefore she cannot fail to win the hearts of the public”, said Puccini at the time. “Why shouldn’t there be two* operas about Manon? A woman like Manon can have more than one lover. Massenet feels it as a Frenchman, with powder and minuets. I shall feel it as an Italian, with a desperate passion.” [*Puccini was only aware of Massenet’s opera, not Auber’s.]

1908

First silent film version, filmed in Italy.

The story is also told in 1914 by HH Winslow, 1926 (director Arthur Robison, Germany), and 1927 (Alan Crosland, USA, under the OTT title When a Man Loves).

1940

Czech poet Vítězslav Nezval writes an adaptation of Manon Lescaut in the form of a drama in verse, which premieres in Prague at the radical D40 theatre.

In Czech literature it is traditionally considered as better than Prévost’s original. The script sold 100,000 copies in ten years.

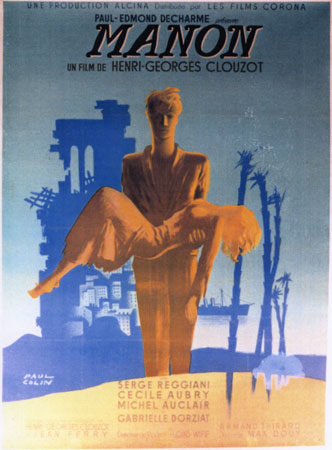

1949

Famous for suspense films, director Henri-Georges Clouzot adapts the story to post-World War II France, turning up its dark overtones: Manon is a former Nazi collaborator, Des Grieux a Resistance fighter and Manon’s brother a black marketeer.

The unscrupulous choices of Manon and her brother, opposed to Des Grieux’s struggles, become a mirror for France’s own divided society.

The film goes on to win the Golden Lion at the 1949 Venice Film Festival. The not-so-subtle US publicity claims “Ooh-la-la! All the screen’s famous sirens stand in the shadow of this tempestuous French sizzler!”.

A more traditional melodrama, the French-Italian Les Amours de Manon Lescaut (directed by Mario Costa) comes out five years later, set in the original time period of the book.

1952

Boulevard Solitude, a one-act opera with contemporary classical influences, by Hans Werner Henze, opens in Germany.

Like the Clouzot film from 1949, it sets the story in post-war France, “in order to reflect the problems of living and loving in a society dominated by greed, money and intolerance” (Gramophone).

1970

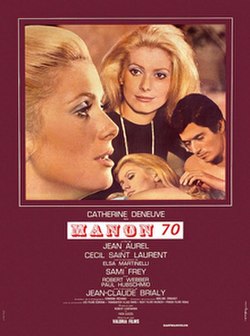

The film Manon 70 comes out, directed by Jean Aurel, starring Catherine Deneuve. Living in the swinging 60s, Manon is fashion conscious, free thinking and sexually liberated – the perfect vehicle for the challenge to social conventions surging at the time.

Serge Gainsbourg writes and sings the title song, from the perspective of a man who loves her: “Cruel Manon… no, you will never know, Manon, how much I hate what you are… I must have lost my mind… I love you Manon”

In 1981, the story is also transposed to modern times by Japanese director Yoichi Higashi.

1974

Kenneth MacMillan premieres his new ballet, Manon, with dancers Antoinette Sibley in the title role, Anthony Dowell as Des Grieux and David Wall as Lescaut, Manon’s brother.

When asked to summarise the plot to a journalist, he replied: “you have a sixteen-year-old heroine who is beautiful and absolutely amoral, and a hero who is corrupted by her and becomes a cheat, a liar and a murderer. Not exactly your conventional ballet plot, is it?” From that non-conventional ballet story, he created a true classic.

MacMillan also once said: “I wanted to make ballets in which an audience would become caught up with the fate of the characters I showed them”. With Manon, he certainly succeeded.

None of the music from Jules Massenet’s opera features in Kenneth MacMillan’s ballet version – MacMillan instead selected some of Massenet’s most well-known pieces, including an orchestrated version of his song Ouvre tes yeux bleus.

1980

This is possibly the most unexpected style for Manon Lescaut to appear in: Japanese pop!

In her hit Anata iro no Manon, Yoshimi Iwasaki sings…

“Oh will you continue to love me

Until you get exhausted and fall on the sand.

Will you give up everything for me?

I am Manon, Manon Lescaut”

We can’t help but wonder if the reference got understood amongst all the disco beats.